It wasn’t until a few days later, when the whole ordeal was over, that I read the fine print on my ticket:

“Seating is first-come, first-served. In case of insufficient seating capacity, passengers will be placed on succeeding schedules that have available seats.”

Such a nice, polite, legalistic way to explain the hell I went through in the Greyhound bus terminal in Raleigh, North Carolina.

I’d gotten on the bus in New Bern, at a scary convenience store and gas station situated on the edge of town. There’s something odd about where they situate these Greyhound stops — so far out of town that you have to have a car to reach them. But people who have cars don’t need Greyhound.

After an hour of waiting at the gas station, the bus itself was pleasant. It was a new one, clean, with fake leather seats, power outlets for charging electronics, and — Hallelujah! — wi-fi. Fewer than half the seats were occupied, so we each had two seats to ourselves. I thought to myself, I can handle 20 hours of this.

About an hour down the road, a man got on at Goldsboro and sat just across from me. He was a slender black man with very short and graying hair, and he was dressed in a curious outfit of all white — white pants, white button-down shirt, white sneakers. His luggage consisted of only a small white trash bag.

For the next hour, I occupied myself with my computer and phone or watched out the window. Across the aisle, my neighbor pulled a small booklet out of his pocket and read some pages, then put it aside and watched out the window, too.

When the bus arrived in Raleigh, I got off with my carry-on luggage — a heavy backpack and a canvas tote full of snacks and water. I retrieved my giant purple suitcase from under the bus and went inside to wait about 30 minutes for my next bus.

I took my time, went to the bathroom, sat and drank some orange juice. When I heard an announcement about my bus, I made my way to Door A in a leisurely fashion, about 15 minutes before its departure. There were four people who had formed a line ahead of me.

What happened next was such a surprise that I experienced it with a sort of shocked detachment. This couldn’t really be happening to me, could it?

A man came to the door, checked the tickets of the first three people, and let them through. He said something I didn’t hear to the fourth person and then turned around.

The man he had spoken to suddenly went beserk, screaming expletives, grabbing the man’s shoulder, and threatening him. The gist of his outburst was, “You can’t keep me off this $@#%!! bus! I have to muster in at oh-seven-thirty in the morning! I serve my $@#%!! country for twenty-three $@#%!! years and this is what I get? You can’t do this, you $@#%!! $@#%!!!”

A woman came out, a station employee. She tried to make peace between the two men, which is when I realized that the one who was checking the tickets was the driver of my bus. He knew that he had three seats, so he let those people on. He was going to step aboard and check for two more seats before he let us on.

Instead, he shrugged. “I don’t have to take you,” he said, walking away. He got on the bus, started the engine, and then drove out of the bus terminal.

Leaving me, an innocent bystander, standing in silence behind an angry veteran who continued screaming and threatening violence. Everyone in the terminal was staring at us.

The woman looked at me sympathetically. “You’ll have to take the next bus at six am.” I stared at her, uncomprehending. It was eleven pm. Then I looked out the door, as if the bus driver was going to come back and say, “Sorry, I forgot that other lady.” He did not.

The station employee said, consolingly, “Don’t worry, I’ll make sure you get on the next one.” I walked slowly away, back to the seating area, in a daze. I was devastated and desperately wanted to cry, but I would have been embarrassed to do so.

It was 11:15 pm, and I was going to have to sit in this terminal for seven more hours. To make matters worse, while the bus had wi-fi and comfortable seating, the terminal had dreadful wire benches and no internet, except for the 10 minutes when a bus with wi-fi happened to be parked outside! To top it off, the room was ruled by a giant, rude television that blared crime shows at top volume.

Adding to the indignity were the two men who came in, propped open all the doors, and blocked them with large trash cans. Then they started asking people to move from their seats. It became apparent that they were going to shove all the benches — and passengers — into a small area, close off the rest, and clean the floors.

That’s when I ended up sitting next to the man in white. I asked if he had just come from work, and he looked confused and said no. “But I thought — your outfit –” I stammered, afraid that I had embarrassed him and was now embarrassing myself. He said something I didn’t quite catch, and when I asked him to repeat it, he shook his head sadly and pantomimed taking a drink. I guessed he meant he’d just gotten out of rehab, so I didn’t probe further.

Over the course of the long night, our conversation grew organically. We compared notes about where we were heading, and how long our trips would take. He was going to “a town so small, you’ve probably never heard of it.” He went on to explain that the closest town was Gastonia, but he had another long layover in Charlotte and wouldn’t arrive until 6 pm. Given that I had seen him board the bus at about 8 pm, that meant over 22 hours to get from one tiny town in North Carolina to another.

I told him I lived on a boat, and he admitted he’d never set foot on a boat. “I only been fishin’ once.” When he asked where I was going, I told him to Florida, and from there to Brazil. He’d never been out of the country in his life.

There was a long, comfortable silence, during which we watched the floor cleaners and a trio of 20-somethings across from us who were behaving erratically.

I asked him how long he’d be staying where he was going. “Oh, I’m going home,” he said. Another silence, then I asked how long he’d been away.

His answer spoke volumes: “90 days.”

Most people would say three months, or maybe “since October.” A few days later, I confirmed my suspicion about his answer by running a search on the internet. There is a state mental hospital in Goldsboro. People who are involuntarily admitted cannot be kept longer than 90 days.

It got very cold in the station with all the doors open, and people around us were grumbling about the cold. I got out a fleece jacket and draped it over my lap. My companion didn’t complain, but I could tell he was cold and had no jacket. I handed him a fleece quillow — a small blanket that converts to a pillow — and suggested that he could use it to keep warm. He accepted it gratefully.

When we finally introduced ourselves, it was after we’d been talking for a couple of hours. “By the way, I’m Thomas,” he said, holding out his hand and chuckling. “I’m Margaret,” I answered, shaking it like we’d just met. With the purple blanket around his shoulders, he looked like an Indian mystic.

After a while, we talked more than we were silent. He wanted to know about the boat and how it operated. Did it have a kitchen and a bathroom? Did I help steer it? Where had we gone in the boat? I asked questions about his family, what places he’d been to, what places he wanted to see. I even got out my laptop to show him photos of Alaska and Yukon, so he could see the beautiful light at midnight on the summer solstice.

Meanwhile, the mood in the bus terminal had gotten ugly. The veteran whose outburst had caused my bus driver to leave was — obviously — waiting for the same bus as me. He erupted every hour or so, yelling belligerently about how unfair this was, then settling down until something set him off again. The 20-somethings also got into repeated altercations with each other and with the employees. The good part was, it got quiet when they went outside to smoke. The bad part was, whatever they were smoking made them more volatile and more hostile when they came back.

It would have been terrifying, except that Thomas was very calm. His influence kept me calm, too.

Sometime after three am, the floor cleaners began moving the benches back, and we had to move again. Thomas picked up my suitcase, all 55 pounds of it, and we found a new spot that was agreeable to both of us. A while after that, they announced his bus. We said a reluctant farewell and exchanged a little hug, both hoping that our paths might cross again someday.

Across the terminal, I could see him waiting patiently in line, the blanket around his shoulders and the plastic bag in his hand. He was standing directly behind the group of obnoxious 20-somethings when things hit the fan.

For the first time all night, the 20-somethings wound up beside the volatile veteran. Like a match to tinder, they set each other off and then banded together against the employees. Suddenly, they were all shouting. The veteran began threatening to beat up the floor cleaners, shoving benches around, and lunging at them. The female employees were trying to placate them, to calm them down, but several of the male employees had reached their limits and were ready to get into fisticuffs with the passengers.

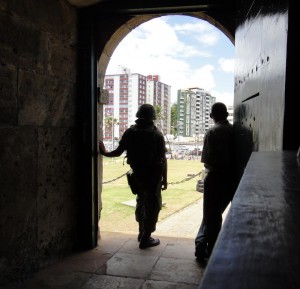

Thomas melted back against the wall, making himself invisible. That’s when the police arrived. They took the difficult passengers outside, and everyone breathed a sigh of relief at the sudden quiet. Then Thomas and about 20 other people boarded the bus to Charlotte, and the room was half-empty.

I missed my ally. Even with the violent people gone, the terminal was still a scary place, and I had a couple more hours to wait. I moved my luggage to a remote corner where I tucked myself under a table on the floor. I could never sleep in the terminal, but at least I could make a fort out of my luggage and hide behind it.

I read my book and waited. When they finally called my bus, I got up and rolled my suitcase over to join the line. To my surprise, there were already six people in line. There was no sign of the station employee who had promised me a seat. Suddenly, I realized that I might not get on the next bus, either. I found myself trembling with fear that I would spend another day in the bus terminal, waiting for the 11 pm bus.

When we boarded the bus, the driver looked twice at my ticket. “You were supposed to be on the 11 pm bus,” he told me. I just stared at him, afraid he was telling me I wasn’t eligible for this bus, either. Then he waved me on. I climbed up the steps and looked down the aisle at a completely full bus. There was only one seat open, beside a Greyhound employee in the front row. She reluctantly moved her bags from my seat.

I had come so close to missing this bus that as we pulled out of the station, I burst into tears. The woman next to me turned to the window and ignored my quiet sobs. For the first time in over 24 hours, I slept.

I didn’t even miss my blanket. I knew that Thomas, my angel in white, was using it to stay warm. He’ll probably never know how valuable his calm companionship was during that long, tough night.